The 23rd of May 1842 may not ring a bell for many, but it marks an important yet often overlooked moment in British and South African history: the Battle of Congella. Although not a large-scale battle, it holds significant importance as the first confrontation between British redcoats and Boer commandos—one of many that would follow. This clash, though forgotten by most, offers key insights into the military strategies and tensions that would define future conflicts between these two forces.

Background to the Conflict

To understand the events of the Battle of Congella, one must go back to the 1830s, when the Boers, descendants of Dutch settlers in the Cape Colony, decided to leave British-controlled territories to avoid what they saw as oppressive laws and taxes. These pioneers, known as the Voortrekkers, moved inland, ultimately clashing with the Zulus. Following their victory over the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River in 1838, the Boers established the short-lived Republic of Natalia in present-day KwaZulu-Natal.

Meanwhile, the British had established a presence at Port Natal (now Durban), originally setting up a trading post during the reign of the legendary Zulu King Shaka. Tensions between the British settlers and the Voortrekkers steadily grew, particularly as the Boers pushed for greater access to the coast. This rivalry came to a head when Boer incursions disrupted local African chiefdoms, causing unrest that threatened British interests in the region.

Recognizing the danger posed by this unrest, Major-General Sir George Napier, the British governor in the Cape, decided to act. In March 1842, he ordered Captain Thomas Charlton Smith to lead a small British force to Port Natal and assert British authority.

The British Arrival at Port Natal

Captain Smith’s task was a daunting one. His force consisted of two companies of the 27th Regiment of Foot, also known as the Inniskilling Fusiliers, along with engineers, artillerymen, and a small contingent of Cape Rifles—a unit made up of Cape-coloured soldiers. In total, this force numbered around 263 men, accompanied by three artillery pieces.

The journey from the nearest British garrison was a gruelling 300 km through uncharted bush with no roads or guides to assist. After a month of slow progress, Smith’s weary force arrived at Port Natal in late April 1842. The local British settlers were relieved to see them, but the Voortrekkers were less than pleased. One of Smith’s first actions was to replace the Boer tricolour flag of Natalia with the Union Flag, a provocative move that deepened tensions between the two groups.

The Boers Prepare for Battle

Unbeknownst to Smith, the Boers were already mobilizing. Andries Pretorius, the leader who had secured victory at Blood River, was assembling a commando force at Congella, a village near Port Natal. Pretorius commanded 364 Boer volunteers, a formidable mounted force with a mastery of marksmanship and skirmishing tactics.

On May 9, 1842, Smith marched with 100 men to Congella and demanded that Pretorius and his men submit to British rule. Predictably, Pretorius refused, deferring the matter to the Boer Volksraad, or parliament. When the answer came back a few days later, it was a resounding rejection of British authority.

Tensions finally boiled over when the Boers raided a British cattle grazing area. This act enraged Captain Smith, who saw it as outright rebellion. He quickly devised a plan to retaliate.

The Battle of Congella

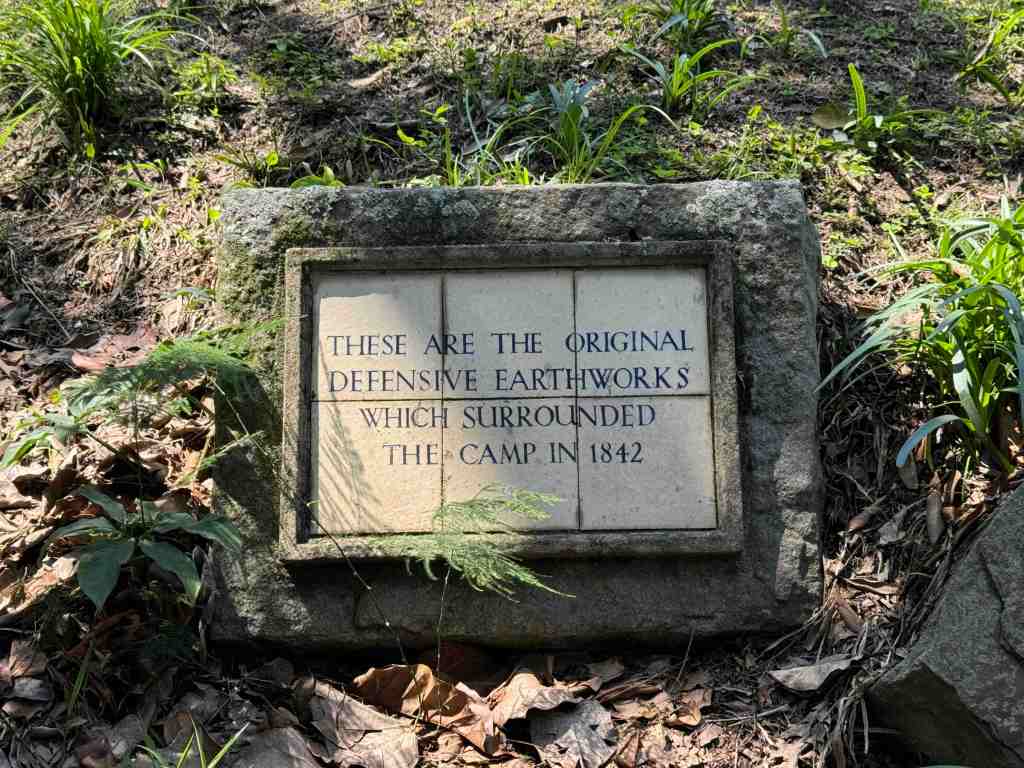

Under the cover of night on May 23, Smith set out with 139 soldiers and two field guns to attack the Boer laager (camp) at Congella. He hoped to catch the Boers by surprise, but his plan quickly fell apart. Despite his attempt at stealth, the moonlit night allowed Boer scouts to spot the advancing British force. The Boers, concealed behind thickets and mango roots, waited patiently.

As the British moved along the beach, the Boers opened fire with deadly precision. The bright moonlight made the red-coated soldiers easy targets. Every time the British stood to reload, they presented the perfect opportunity for the Boer marksmen.

The British suffered heavy casualties in the opening minutes of the battle. Lieutenant Wyatt, riding on a gun carriage, was struck by a musket ball and killed instantly. By the time the skirmish was over, British losses were devastating: between 18 and 22 men were dead, with six more missing. The Boers, on the other hand, had only a handful of casualties.

This battle marked the first time British soldiers faced the Boers in combat. It was a rude awakening for the British, who were unaccustomed to the hit-and-run tactics of the mounted Boers. The Boers, operating like mounted infantry, would ride within range, dismount, and use their rifles to deadly effect before retreating out of range. In the rugged South African terrain, this guerrilla-style warfare would prove brutally effective.

The Siege of Port Natal

Following the defeat at Congella, Captain Smith’s forces retreated to their makeshift fort at Port Natal, now on the defensive. The Boers, knowing their strengths and weaknesses, did not attempt a full-scale assault. Instead, they laid siege to the British fort, bombarding it with artillery and small arms fire while cutting off supplies in an effort to force a surrender.

Desperate for reinforcements, Smith turned to a local settler named Dick King, known for his toughness and survival skills. On May 25, King and his Zulu servant Ndongeni slipped through the Boer lines and set off on a remarkable 960 km journey through the South African wilderness to the British garrison at Grahamstown. After ten days of hard riding, King reached his destination and collapsed from exhaustion, having completed one of the most legendary rides in South African history.

The British Reinforcements Arrive

Thanks to King’s heroic efforts, a relief force of 800 British soldiers was dispatched from Grahamstown. Arriving aboard HMS Southampton and Conch, they landed at Port Natal on June 26, 1842. The Boers, realizing they could not win against such overwhelming numbers, wisely withdrew. The Union Flag was raised once again over Port Natal, and British control over the region was solidified.

In the years following the battle, the British formally annexed Natal in 1845, much to the dismay of the Boers, who once again packed up and moved further inland. The Battle of Congella may have been small, but it set the tone for future conflicts between British imperial forces and Boer commandos—conflicts that would culminate in the Anglo-Boer Wars of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Legacy of the Battle

Although the Battle of Congella is often overlooked in the grand sweep of history, it holds significant importance as the first of many confrontations between British regulars and Boer fighters. The Boer style of warfare—marked by their expert marksmanship, mobility, and guerrilla tactics—would shape the nature of conflict in the region for decades to come. For the British, Congella was a bitter lesson in the difficulties of fighting a determined and resourceful enemy on unfamiliar terrain.

This forgotten battle offers us a glimpse into the early stages of a long and bloody struggle that would forever change the course of South African history.

—

For more stories like this please be sure to sign up for my mailing list below or subscribe to the Patreon Page for early access to ad-free videos.