This is the fourth part of my series examining the Peninsular war through the eyes of the British soldiers.

For the previous instalment, about the battle of Rolica, please follow this link.

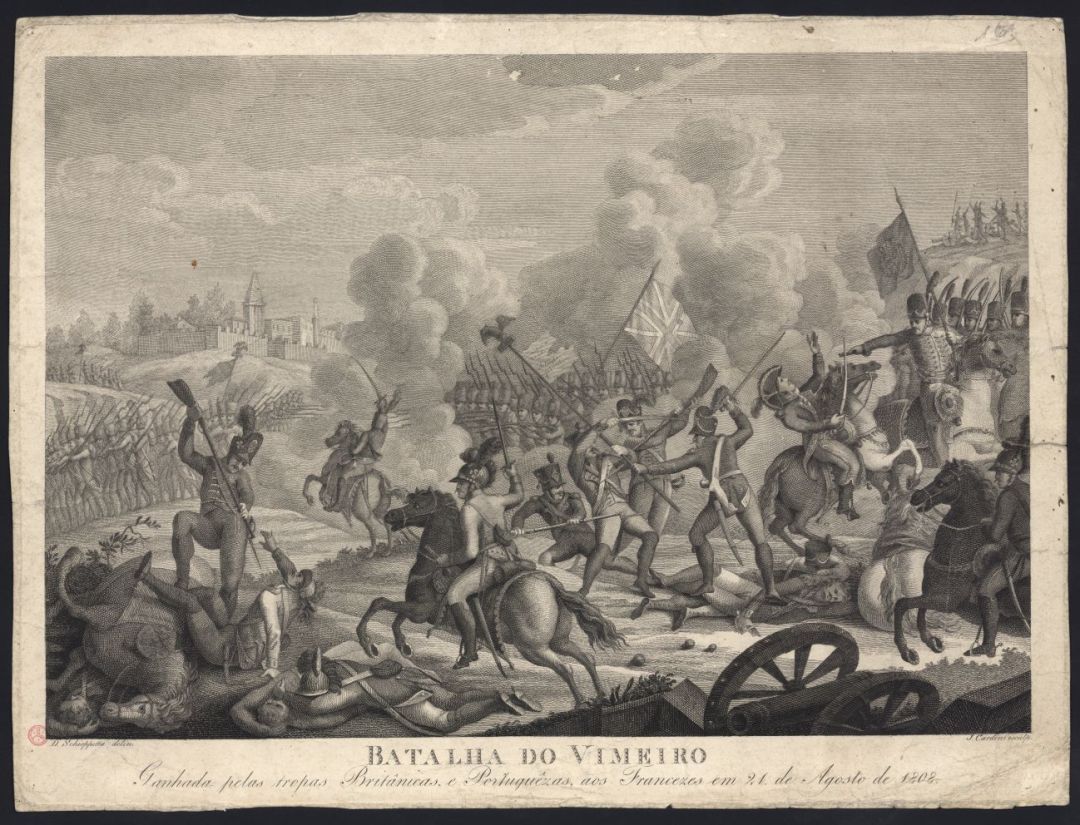

Under a broad blue sky, dotted with thin wispy clouds the British army hastily pulled on their boots and grabbed their weapons. Bugles sounded and Sergeants bawled at the men. There were dust clouds on the horizon, the French columns were advancing. It was 9 am on the 21st August 1808.

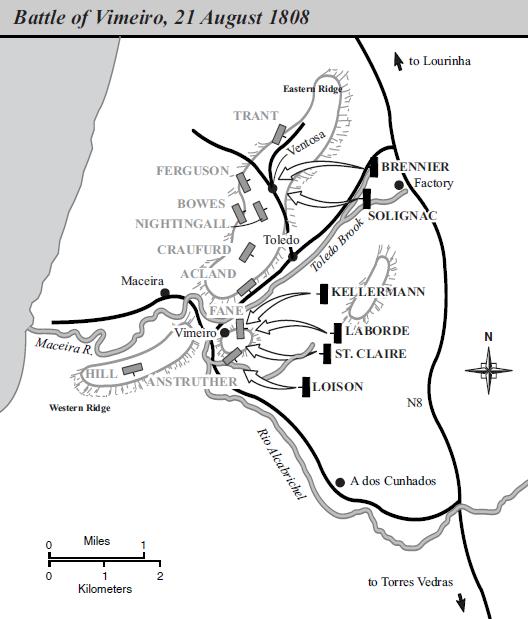

The British force was positioned around the village of Vimeiro. They had been camped here while two fresh brigades under Generals Acland and Anstruther had disembarked along the coast nearby the previous day. Wellesley’s army now numbered about eighteen thousand men divided between eight brigades, plus the Portuguese under Colonel Trant.

They were still waiting for the arrival of Sir John Moore and his 10,000 troops en route from Scandinavia.

Wellesley had placed his men along three key features. On the eastern ridge, positioned north to south were the Brigades of Ferguson, Bowes, Nightingall, Crauford and Acland with Trant’s Portuguese watching their extreme northern flank. On the hill in front of Vimeiro village were Fane’s and Anstruther’s Brigades while Hill’s men defended the army’s other flank on the western ridge.

With the reinforcements had also arrived Sir Harry Burrard who was set to take command of the British force until Sir Hew Dalrymple’s arrival. This meant that technically Wellesley was no longer in command, but Sir Harry had decided to spend the night of the 20th/21st onboard ship so that he could finish writing his letters and therefore was not present for the opening of the battle. But his instructions to Wellesley forbidding any advance until all of Sir John Moore’s troops arrived had already annoyed Wellesley and limited the scope of his plans for the coming battle. Sitting back, handing the initiative to the enemy and allowing them freedom of movement is rarely a prudent course in warfare.

The French had also been heavily reinforced after the battle of Rolica and now numbered thirteen thousand men, commanded by General Junot himself. He’d organised his troops into two infantry divisions under Generals Delaborde and Loison respectively. There was also a reserve of infantry and a cavalry division commanded by General Margaron, as well as twenty-three guns.[1] They were determined to drive the British into sea.

Like all French Generals of the time, used to continuous success and expectant of victory, Junot had little respect for the prowess of his enemies and immediately decided to throw his force into a frontal attack.

It was a move that was anticipated by the redcoats, John Patterson of the 50th Regiment and his men had been counting on it,

“Junot, who was the General in chief, held the British in much contempt, and endeavoured to impress upon the minds of his followers, that their antagonists were a set of raw campaigners, wholly devoid of military skill. From the testimony of some deserters, who came into our lines, we learned, that the Marshall intended to give us a dusting, and to brush the pipeclay out of our jackets. This cavalier determination of the Marshal afforded no small amusement to our soldiers who promised themselves some good sport. . .They resolved gratefully to return the compliment, by trimming the whiskers of his gallant veterans, and powdering their mustachios, in so artist-like a manner, that the aid of a friseur should no longer be required.[2]”

Junot directed four battalions of Brennier’s Brigade and a Regiment of dragoons against the eastern ridge but they became entangled in an assault course of rocks and streams.

Meanwhile, before Brennier had even got within striking distance of the ridge, Junot ordered an assault against Vimeiro village, defended by the Brigade’s of Fane and Anstruther.[3]

The French artillery opened fire and their infantry moved forward in a dense mass, protected by a thick swarm of skirmishers. Two columns advanced menacingly towards the British, their flanks protected by cavalry. Classic French tactics that had dominated European battlefields for the last decade.

The British guns responded and as usual Ben Harris of the 95th was there,

“The first canon shot I saw fired, I remember was a miss. The artilleryman made a sad bungle, and the ball went wide of the mark. We were all looking anxiously to see the effect of this shot; and another of the gunners (a red haired fellow) rushed at the fellow who had fired, and in the excitement of the moment, knocked him head over heels with his fist, ‘Damn you for a fool,’ he said, ‘what sort of shot do you call that? Let me take the gun.’ He accordingly fired the next shot himself . .and so truly did he point it at the French column on the hillside, that we saw the fatal effect of the destructive missile, by the lane it made and the confusion it caused.”

Ben and his colleagues in the 95th were sent forward to break up and unsettle the French but were gradually pushed back. Behind them the 50th Regiment, nicknamed the black cuffs, formed line – all of their 900 muskets ready to greet the enemy. Captain Patterson was amongst them and takes up the story,

“The 50th regiment, commanded by Colonel George Townsend Walker, stood firm as a rock, while a strong division under General Delaborde continued to advance at a rapid step, from the deep woods in our front, covered by a legion of tirailleurs, who quickened their pace as they neared our line. Walker now ordered his men to prepare for close attack, and he watched with eagle eye the favourable moment for pouncing on the enemy. When the latter, in a compact mass, arrived sufficiently up the hill, now bristling with bayonets, the black cuffs poured in a well directed volley upon the dense array. Then, cheering loudly, and led on by its gallant chief, the whole regiment rushed forward to the charge, penetrated the formidable columns and carried all before it.”[4]

The French column was sent reeling back in confusion. The second French column under General Charlot suffered a similar fate as it was raked with fire from Anstruther’s troops which had been well concealed by the landscape.

Junot’s first attack had failed miserably. Casualties had been heavy, both General’s Delaborde and Charlot had been wounded, and all of their accompanying guns had been captured.[5] Junot was now concerned for the advance of Brennier against the British left flank and sent them three more battalions and six guns.

In haste, he decided to gather his reserves and throw them forward along the same road that Delaborde had just followed to defeat. Advancing in platoon sized columns the French were hammered by Howitzers firing the new British shrapnel shells which rained musket balls and pieces of shell casing onto them, tearing ragged gaps in the advancing columns.

Ben Harris noted at the time what fine looking men the Frenchmen were with their red shoulder knots and tremendous looking moustaches,

“As they came swarming upon us they rained a perfect shower of balls, which we returned quite sharply. Whenever one of them was knocked over, our men called out ‘There goes another one of Boney’s invincibles.’”

These “Invincibles” were struck with the converging fire of three infantry battalions, turning the hillside into a charnel house of dead and wounded Frenchmen.

Meanwhile, General Kellermann had lead two other battalions of Grenadiers around Fane’s left flank and into the village of Vimeiro. Anthony Hamilton of the 43rd and his comrades were ready for them,

“A column strongly supported by artillery was again sent forward to gain possession of the village of Vimeiro. Here our Regiment, the 43rd, was posted, close by the road that entered the village. The enemy advanced upon us with determination and valour, but after a desperate struggle on our part, were driven back with great slaughter. It was not only a hot day but also a hot fight, and one of our men by the name of McArthur, who stood by me, having opened his mouth to catch a little fresh air, a bullet from the enemy at that moment entered his mouth obliquely, which he never perceived, until I told him his neck was covered in blood. He however kept the field until the battle was over.[6]”

Viewing the fight in the village from nearby was Lieutenant Charles Leslie, of the 29th Regiment,

“While watching with intense interest the progress of the enemies attack on our centre, we observed a party of the 43rd Light Infantry stealing out of the village and moving behind a wall to gain the right flank of the enemy’s lines, on which they opened a fire at the moment when the enemy came in contact with our troops in position. The French had been allowed to come close, then our gallant fellows, suddenly springing up, rapidly poured on them two or three volleys with great precision, and rushing on, charged with the bayonet. We soon had the satisfaction of seeing the enemy broken and retreating in the utmost haste and disorder.”[7]

At this point, with the French battered and falling back, Colonel Taylor lead his 20th Light Dragoons into the charge, they sabred their way through the retreating French but became over excited and over stretched. Captain John Patterson witnessed what happened next,

“The horsemen, unsupported, charging the enemy with impetuosity, and rashly going too far, were involved in a difficulty of which, in their eagerness to overtake the stragglers, they had never thought; for, getting entangled among the trees and the vineyards, they could do but little service, and suffered a loss of nearly half their number: The brave commander being also one of those who fell in that desperate onset.[8]”

As the fighting around Vimeiro hill now petered out the focus of the battle shifted to the British left on the Eastern ridge. Here William Lawrence of the 40th Regiment had already had a busy morning,

“The right of our line was engaged at least two hours before a general engagement took place on our side, which was the left, but we were skirmishing with the enemy the whole time. I remember this well, on account of a Frenchman and myself being occupied in firing at each other for at least half an hour without doing anyone any injury; but he took a pretty straight aim at me once, and if it had not been for a tough front rank man that I had, in the shape of a cork tree, his shot must have proved fatal, for I happened to be straight behind the tree when the bullet embedded itself in it. I recollect saying at the time, ‘Well done, front rank man, thee doesn’t fall at that stroke,’ and unfortunately for the Frenchman, a fellow comrade who was left handed came up to me very soon afterwards and asked me how I was getting on. I said badly and told him there was a Frenchman in front. . .I pointed out the thicket behind which the Frenchman was, and he loaded his rifle so as to catch him out in his peeping manoeuvres. . .Mr Frenchman again made his peep around the bush, but it was his last, for my comrade, putting his rifle to his shoulder, killed him at the first shot.”

The Brigades on the French right under Brennier and Solignac finally got into position and launched their columns up the steep slope. Solignac’s men struck first, but he had underestimated the strength of the British who had been lying down behind cover. The red coats let the French get to within one hundred yards before General Ferguson ordered the troops up and forward in line. They then let rip with a devastating volley of fire. Three thousand muskets barked in unison, a wave of fire that tore the French column to pieces. Thomas Pococke was with the 71st regiment,

Thomas Pococke was with the 71st regiment,

“We gave them one volley and three cheers – three distinct cheers. Then all was death. They came upon us crying and shouting, to the very point of our bayonets. Our awful silence and determined advance they could not stand. They put about and fled without much resistance. At this charge we took thirteen guns and one general.[9]”

As the British celebrated their victory and counted their captured guns Brennier’s Brigade, which had been missing all morning in the rugged terrain, suddenly emerged unobserved from a deep ravine. He threw his infantry at the 82nd and 71st regiments while his cavalry tried to outflank them to the east. The British were driven back and the guns recaptured. Witnessing this unexpected turn of events the 29th Regiment sprung into action. Charles Leslie takes up the story,

“We were instantly ordered to form four deep, which formation afforded the advantage of showing a front to meet the enemy in line, and at the same time sufficient strength to resist cavalry. On the enemy approaching the low ground a destructive fire was opened upon him by the 71st Regiment and the light companies of the 29th and 8th Regiments, which had been lying there concealed by the willow beds and bushes, unknown to us and much less to this column of the enemy, whom, after returning an irregular fire, broke and fled in utmost disorder.[10]”

Every single French infantry battalion had now been broken,[11] they had no more reserves and began streaming away from the field as quickly as they could. The site of the French in headlong retreat had a been a rare one on European battlefields in recent years and the redcoats were elated. John Patterson recalls,

“As far as the eye could reach over the well planted valley, and across the open country lying beyond the forest, the fugitives were running in wild disorder, their white sheepskin knapsacks discernible among woods far distant. . . The ground was thickly strewn with muskets, side arms, bayonets, accoutrements and well-filled knapsacks, all of which had been flung away as dangerous encumbrances.[12]”

By this point Sir Harry Burrard was now on land, he’d astutely left Wellington in charge as the fighting raged but now the French were beaten and streaming to the rear he made his mark on the day.

Wellesley could see that there was now a genuine chance to pursue the French and destroy them as fighting force. He had thousands of fresh troops, the brigades of Hill, Crauford and Bowes had not suffered a single casualty. Their morale was high and they were desperate for their chance of glory.

Wellesley galloped his horse to Burrard, “Sir Harry,” he said, “now is your chance. The French are completely beaten. . .You take the force here straight forward and; I will bring round the left with the troops already there. We shall be in Lisbon in three days.[13]”

But Sir Harry was a General of the old school, he was understandably concerned about lack of supplies and transport as well as the weakness of his cavalry. Instead of grabbing the initiative and destroying the French completely he ordered the army to halt and wait for Sir John Moore’s troops.

Thus the British were unable to complete their victory. They had shattered Junot’s army, breaking every column that was sent against them. They had inflicted eighteen hundred French casualties and taken three to four hundred unwounded prisoners. Their own casualties were one hundred and thirty-five dead and over five hundred wounded, a high proportion coming from three regiments: the 50th, 43rd and the 71st who had all been key to victory.

At the close of battle, Harry Ross-Lewin of the 32nd regiment went to explore the battlefield, witnessing the bloody aftermath of the struggle,

“Upon entering the churchyard of the village of Vimeiro, my attention was arrested by very unpleasant objects – one, a large wooden dish filled with hands that had just been amputated, another, a heap of legs placed opposite. On one side of the entrance to the church lay a French surgeon who had received a six pound shot in the body. The men who had undergone amputation were ranged around the interior of the building. In the morning they had rushed to combat, full of ardour and enthusiasm, and now they stretched pale, bloody and mangled on the cold flags, some writhing in agony, others fainting with loss of blood, and the spirits of many poor fellows among them making a last struggle to depart from their mutilated tenements.[14]”

Outside the scenes were equally as disturbing,

“A great number of the 43rd lay dead in the vineyards which part of that regiment had occupied; they had landed (in Portugal) only the day before, and they looked so clean, and had their appointments in such bright and shining order that, at the first view, they seemed to be men resting after a recent parade rather than corpses of the fallen in a fiercely contested engagement. This corps which suffered so severely had passed us in the morning in beautiful order, with their band playing merrily before them. How many gallant fellows that we then saw marching to the sound of national quicksteps, all life and spirits, were before evening stretched cold and stiff on the bloody turf.”[15]

The battle of Vimeiro did more for British pride and stature than any European land battle since Malplaquet. The classic French tactics: a swarm of tirailleurs ahead of a dense column with artillery support had failed against the British thin red line of well drilled and astutely commanded troops. The two deep line had shown its worth, wrapping itself around the French columns and hammering them with volley fire before breaking them with a well-timed bayonet charge. Wellesley had shown his understanding of the modern battlefield making sure his men kept under cover and out of site as much as possible and that his flanks were well secured, tactics that were to help make him one of the greatest British Generals of all time.

If you have enjoyed this article the you may want to see more of my Peninsular war writing. Please follow this link.

[1] A History of the British Army – Vol VI – (1807-1809) by Hon Sir John William Fortescue. Kindle edition, location 3348.

[2] Adventures of Captain John Patterson. Captain John Patterson. P 37.

[3] A History of the British Army – Vol VI – (1807-1809) by Hon Sir John William Fortescue. Kindle edition, location 3432.

[4] Adventures of Captain John Patterson. Captain John Patterson. P 45-46.

[5] A History of the British Army – Vol VI – (1807-1809) by Hon Sir John William Fortescue. Kindle edition, location 3466.

[6] Hamilton’s campaign with Moore and Wellington during the Peninsular war. By Anthony Hamilton, 1847. P.14.

[7] A record of the 29th Foot by Colonel Charles Leslie, K.H. http://www.worcestershireregiment.com/wr.php?main=inc/h_29th_foot_1807to1813.

[8] Adventures of Captain John Patterson. Captain John Patterson. P 47-48.

[9] Journal of a Soldier of the 71st Regiment From 1806-1815. By Anon. “Thomas”. Kindle edition, location 404.

[10] A record of the 29th Foot by Colonel Charles Leslie, K.H. http://www.worcestershireregiment.com/wr.php?main=inc/h_29th_foot_1807to1813.

[11] Wellington in the Peninsular by Jac Weller. Kindle edition, 2012. Location 695.

[12] Adventures of Captain John Patterson. Captain John Patterson. P 46-47.

[13] A History of the British Army – Vol VI – (1807-1809) by Hon Sir John William Fortescue. Kindle edition, location 3515.

[14] With the Thirty-Second in the Peninsular and other campaigns. By Harry Ross-Lewin. P. 109.

[15] With the Thirty-Second in the Peninsular and other campaigns. By Harry Ross-Lewin. P. 110.

2 thoughts on “The Peninsular war part 4: The battle of Vimeiro”